People incorrectly using “big words” has always been one of my pet peeves. When I see a fancy word used incorrectly in a cover letter (and I have seen way too many… we’re librarians people!!!), I cringe. There’s something about it that rubs me the wrong way; like someone is trying to be something they’re not… putting on airs. Last year, I helped lead a campus-wide assessment of upper-division student writing skills as part of my service on the Institutional Assessment Council. Again, the mis-use of big words reared its ugly head. But my awesome colleague, Annie, a writing coordinator for University Studies, got me to see this error in a different light. She talked about the idea of “stretch.” This is the notion that students who are trying to grow as writers will exhibit certain types of errors, one of which is the mis-use of sophisticated vocabulary. She taught me that not all errors are equally damning and that the number of errors is less important than the types of errors. I found the notion of stretch errors fascinating and was reminded of the idea when I saw it described in the Inside Higher Ed article “The Ballad of the Red Pen.”

My fellow Oregonian, Anne-Marie Dietering, wrote about the concept of stretch as well and asked where we might see stretch in information literacy. One place that immediately came to mind is in going beyond very basic keyword searching. I sometimes have students do pre-session activities before I work with their class. It gets them learning and doing before I work with them and it gives me an idea of where they are and what I should focus on. The pre-assignment often has students watching a video on developing a search strategy and then has them do some searching on their own topics. When I see their work, I see some students struggling to use the techniques they’ve just learned. You see students trying to use quotes, but using them around single words or entire sentences. You see them using Boolean operators, but in weird ways that wouldn’t quite get them what they needed. I’d see these errors and feel a lot better about those students than the ones who still used the same brute-force tactics, even if those brute-force tactics were used more correctly. While the results were not great for the students who exhibited stretch, at least they are trying to apply more sophisticated techniques. And since I had yet to meet with the class, I could highlight those areas where I saw stretch errors happening to help the students get beyond them.

I also think that you see a lot of stretch errors in students starting to use paraphrasing instead of just directly quoting sources and in integrating sources meaningfully into their papers. Using sources is an art (one in which many of us are still working to improve) and it’s not exactly shocking that research paper newbies would struggle with this. As Ann-Marie mentions in her post, patch-writing (which is often considered plagiarism disguised as paraphrasing) is talked about as if it’s a terrible crime, when maybe it’s the natural first step in students learning how to use sources. It’s a a stretch error. The bigger question is: how do we get them past it?

Another stretch error we see is the use of sources that don’t really further an argument or do much of anything other than meet a requirement for using sources. I hear instructors frequently complain that students will use sources that are almost totally unrelated to their topic and just pull out a single quote that is vaguely related to their paper but doesn’t further their argument. In the Freshman research paper assessment we did last month, one student wrote a paper on current media consumption habits amongst young people by citing nothing published after 1976.

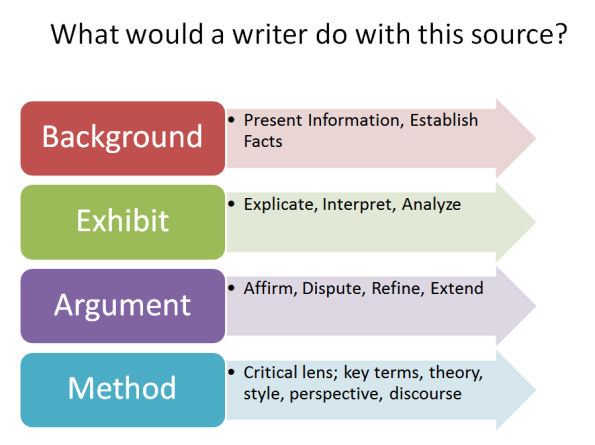

I often wonder if students really understand the purpose of evidence in a research paper. We talk so much about “sources” and having a certain number or type, when, really, we tend to skip the part where we ask “what evidence do you need to make your case or answer your question?” Students jump straight from choosing a topic to searching for sources (or worse, they write the paper and then look for sources), but if they don’t first think about what evidence they need, they won’t know what sources are truly relevant or good for their paper (beyond meeting the instructor’s requirement for x number of peer-reviewed sources). I think the problems with using sources come when students have a random bunch of sources that don’t really further their argument or increase their understanding of the topic. Barbara Fister wrote about this and, similarly, found fault with the way librarians and disciplinary faculty tend to teach sources. Like one commenter on ” Barbara’s post, the wonderful Kate Ganski at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee (whose blog I love), I’ve also started using the BEAM model for teaching sources because it’s focused more on how sources are used. And I’ve also been focused more on having students brainstorm what types of evidence they might need to better understand their topic or make their case before they even start thinking about what types of sources they need to get that evidence.

Reading and assessing student papers has been really enlightening for me. It’s helped me see the errors students make and make better sense of what they mean than when I hear about those errors second-hand from instructors. Understanding why students make the errors they do is the key to helping them get beyond those errors. It makes me happy to be able to see a straight and clear line between the assessment work I’ve been doing and my improvement as an instructor. Assessing student papers often doesn’t yield the sort of evidence librarians wish they had (like demonstrating the effectiveness of library instruction), but the more information you glean about how students are applying what they’ve learned the clearer you are on what you need to do in the classroom, in building learning objects, and in working with disciplinary faculty.

Image source: BEAM Model slide by Kate Ganski

[…] Website of librarian, writer, speaker, consultant and LIS educator, Meredith Gorran Farkas. Includes the popular Information Wants to be Free blog. […]

“We talk so much about “sources” and having a certain number or type, when, really, we tend to skip the part where we ask “what evidence do you need to make your case or answer your question?”

I’ve had this sense for a long time too. But every time I try to come up with a way to address this with teachers, I get the feeling that I’m over stepping my territory.

Interesting read and thoughts, thanks!

I agree, Carleen, it can be difficult. I find when I take the “evidence” approach with students, I still have to lead with the caveat that “you also need to use the sorts of sources your instructor has required.” Fortunately, there usually is overlap over what they come up with for evidence needs and what their instructor wants.

Sorry, but had to point out that in a post that cringes about other people misusing words, I cringed at the bad punctuation in your very first paragraph!

We all have things that drive us crazy. For me, it was misuse of words and for you, it’s punctuation. For other people it’s use of certain words, people who talk with their hands, etc. It’s a personal reaction.

I think recognizing our own imperfections is helpful in becoming more sympathetic towards those in other people.

Understandable. 🙂 But after years of reading Meredith’s blog, I can tell you that her posts are exceptional compared to others I have read. In fact, read one of my posts and you’d likely loose sleep over my mistakes.

Errors and Expectations: A Guide for the Teacher of Basic Writing by Mina P. Shaughnessy (Oxford, 1977) changed forever my understanding of student errors and led to my appreciation for how much we can learn by being observant of them. Somewhere I even have a draft of multiple research project designs for using her research approach and applying it information literacy … should that be our next project? 🙂

Sounds fun, Lisa! I certainly work with enough novice researchers (i.e. Freshman) to make it do-able.

[…] meredith.wolfwater.com/wordpress/2013/09/10/understanding-why-errors-happen-is-more-important-than-s… […]

I would be interested to hear (or see) some ways that you have used the BEAM model in library instruction sessions, whether it be in a one-shot session or a more integrated fashion.

I’ll be reading the article you linked, as well as searching for what Kate Ganski has written, but I’d appreciate a few helpful places to start looking.

Hi Chris! Mainly I’ve used it in a discussion to start students talking about HOW they might use their sources. I explain the model and then ask students to think about what types of evidence they need and how they will use each. I also created this video based on BEAM (which I’m not in love with, but I don’t have time to do more fluffing) as part of a course-integrated tutorial I’m building http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3yYBZ8W1DHE.

[…] The art of using sources correctly […]

[…] Reflection: Week 8 link […]