So many of us struggle with determining priorities in teaching. Few of us have a workload that would allow us to do everything we would like to do. We hear stories about embedded librarian programs, librarians who were able to co-grade student papers with a disciplinary faculty member, libraries that have co-taught entire classes, etc. and we think: wow, I’d love to do that. But can we? And then that goes to the broad vs. deep argument. Is it better to teach a small number of students very deeply or reach a large number of students in a more superficial way. Neither option is particularly satisfying. There are so many interesting models for librarians to provide instructional services, but not every one is a right fit for the population or our time. And there are certainly times when we can’t do what would be the best fit for the population because of our time. We can’t ignore that reality.

I’ve been thinking of this a lot lately in light of the fact that we recently hired an instructional designer to ramp up our production of learning objects. Learning objects certainly provide libraries the potential for providing instruction to many more people than we can with one-shots or any physically present instruction, but they’re not always a substitute for face-to-face instruction. Sometimes they provide more and sometimes less. And one of the biggest problems I’ve seen with learning objects is that they are not often embedded in classes or at students’ points of need. I’ll talk about this more in a future post.

And there are also a lot of bad learning objects. I’ve become increasingly convinced that screencasts are not the right fit for teaching people how to use online databases. It’s very difficult while watching a video to work with a database. It’s also difficult to scan for just what content one needs when they are actually using the database. Lori Mestre’s study on learning styles and learning objects confirmed my suspicions when she found that students using a static HTML tutorial were better able to do database searching than a group that watched a Camtasia screencast because they could go back and forth between the tutorial and the database and practice what they were learning while they were learning.

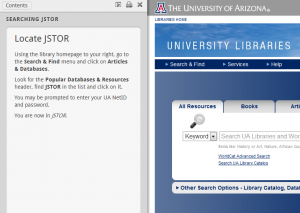

This is why when I saw the University of Arizona’s Guide on the Side software I was instantly smitten. You can read more about the Guide on the Side in my most recent American Libraries column. The idea of having the instructional content right beside a live web page that students can use to search is brilliant! Being able to switch between a window with a tutorial and a window with a database isn’t terrible, but having the tutorial actually within the same window so it’s always in your line of sight, always beside you, makes it even easier for students to practice what they’re learning.

I plan to write more about these issues in future posts; not just about learning objects, but about ways of rethinking what we can do instructionally in light of often-present limitations. It’s something I struggled with here and also at the small private University where I was previously. Few of us haven’t ask these questions. Is the one-shot model a good fit? Is a deeper (embedded?) model better? Should we all be teaching for-credit term-long courses? Does a “train the faculty” or “train the TA” model make more sense? Should we replace more of our teaching with learning objects and, if so, which classes need physical presence and which don’t? And how do we get those learning objects used when students aren’t required to come in for an instruction session? I don’t have the answers, but I’ll be exploring these questions in future posts to this blog.

Congrats on your one year anniversary at PSU! I have always liked the idea of giving students the opportunity to practice what they learn from a library session.

When I was at UI&U in 2006, I developed a tutorial primarily based on Western Michigan University’s Open Publication Tutorial SearchPath (http://www.wmich.edu/library/searchpath/docs/opl/license.html) which used frames to guide students through searching exercises similar to your example at the University of Arizona with instructions on the left and the live site on the right. Because the tutorial was at that time required for certain programs to take, I felt that it needed some interactivity to engage students. It is still up and running. Here’s an example of one of the practice searches. http://www.myunion.edu/library/tutorial/mod5/20-live-keyword-search.html.

Hope our paths cross again soon. Miss you in VT!

It’s very timely that you are writing this – I was just down at UofA and spoke with some of their librarians about Guide on the Side. At my institution we’ve been having quite a few discussions about the best role of instruction. But I think conversations with other institutions is important as well. What works best for PSU might not work best for my institution but it might give me ideas on how to adapt. How can we have more of these conversations?

Pingback: Instruction & Outreach Committee (IOC) » Instruction book and blog post - UCSD Libraries

Pingback: Reflective Statement | MVR's Online Learning Journey

Pingback: The Creative Librarian » No, we can’t do it all | Information Wants To Be Free