I know a lot of librarians get mad about poorly informed articles about libraries all the time. It’s rare that I ever really get truly angry about an article. I expect nothing less from the NY Times at this point than both-side-ism and “Nazis! They’re just like us” articles. I expect too-late, tone-deaf statements from ALA. I expect Library Journal to not to live up to the ideals they spout in articles and trainings. But I’ve come to expect excellent scholarship and criticism from In the Library with the Lead Pipe. They have published some of the most important articles of the past decade, including Fobazi Ettarh’s “Vocational awe and librarianship: The lies we tell ourselves” and Nicola Andrews’ brilliant brilliant brilliant “It’s Not Imposter Syndrome: Resisting Self-Doubt as Normal for Library Workers.” I think that’s why I was so shocked to read the latest article which is not only deeply insulting to library workers, but is also not up to the stated standards of the publication. And in this post, I am calling for the retraction of “Conspiratorial Thinking in Academic Libraries: Implications for Change Management and Leadership” by Catherine B. Soehner and Chanel Roe.

When I first saw this article, I thought it was about whether librarians, those who often teach information literacy, are susceptible to popular conspiracy theories. But no, it’s about conspiracies within the organization. I hadn’t actually heard of the concept “organizational conspiracy theory” before. The definition they use is from the study whose survey they also utilized: “notions that powerful groups (e.g., managers) within the workplace are acting in secret to achieve some kind of malevolent objective.” The authors go on to describe how conspiracy theories often arise in people who do not understand what is happening, feel a lack of control, and need to maintain a positive self-image in the face of change. Here is the example they offer:

Imagine that a library dean decides to remove a reference desk, consolidate the reference and circulation functions at the circulation desk, and remove librarians from answering front line reference questions, replacing them with well-trained support staff. While the dean may have expressed her reasons for this change, librarians might understandably feel a loss of control over their work, a lack of understanding of the reasons for the change, and a need to maintain a positive self-image by imagining that library administration is completely wrong and that the librarians would never do anything as evil as this (i.e., we, the librarians, are much better than those in administration, thus maintaining a positive self-image).

Soehner & Roe, “Conspiratorial Thinking in Academic Libraries: Implications for Change Management and Leadership”

Hmmm… so the authors seem to be suggesting that it’s reasonable for a library dean to unilaterally make all of these changes. I would certainly hope that any change like this would be based not only on feedback from the people in both reference and access services who regularly staff those desks, but also feedback from the college/university community, especially students. But that’s not at all how this sounds. It sounds like their model is that change is created by dean-types and happens to library workers. We plebes are simply pawns who are moved around the board by the folks in charge. We are the “recipients of change.” And of course someone in such a situation would feel both confused and out of control and may also feel a marked lack of autonomy which may impact their self-concept (huh, these characteristics sound a lot like the recipe for burnout, no? Funny that…). The authors write “organizational conspiracy theories are a likely part of how employees in libraries cope with rapid change.” I’ve heard this “librarians are against change” trope long enough (Library 2.0 anyone???) to know that it’s mostly bullshit. What people often reject is change that isn’t user-centered or change that hasn’t been well-discussed. That’s not to say that some people aren’t also tied to certain ways of doing things, but I haven’t worked with a single library worker who wasn’t willing to shift the way we did things when they understood it was going to help students. People also sometimes reject change when it’s foisted upon them with no discussion or real opportunity to offer feedback (not the performative listening so many of us are asked for these days). Again, totally reasonable responses!

So this study sought to better understand organizational conspiracy theories in libraries in order to make suggestions to support change leadership in libraries. They sought to prove their hypothesis that “librarians and staff in academic libraries have strong organizational conspiracy beliefs, that these beliefs decrease job satisfaction, and that this combination of belief and decreased job satisfaction contributes to a decrease in organizational commitment and contributes to an employee’s intention to leave their job.” Now at this point, I was really wondering exactly what they meant by organizational conspiracies and how they were going to measure it, so I’m going to jump ahead to their survey, which again, they took from a 2017 study with an impressive 64 citations, though if you look at them, you’ll find that 15 of the first 20 citing articles listed were also authored by at least one of the two authors of the original study… sigh…). Here is the list of Likert-scale questions that measured “organizational conspiracy beliefs:”

- “I think that a small group of people in my workplace makes all of the decisions to suit their own interests.

- Employees in my workplace are not always told the truth by those in charge.

- I think that a small group of people in my workplace secretly manipulates events.

- I think that the powerful people in my workplace conceal important information from employees.

- I think that very important things happen in my workplace, which employees are never informed about.

- I think that the powerful people in my workplace often do not tell employees the true motives for their decisions.

- I think that there are secret groups within my workplace that greatly influence decisions.”

First of all, wow those are really redundant. They seem to center around just two things: concerns about decision-making and concerns about transparent communication. Those are common and legitimate concerns in many libraries! Call me a conspiracy theorist, but I don’t just think a small group of people in my workplace make most decisions, that’s literally how my place of work works! And I don’t just think that the people in power in my library conceal information; they actually do. Do I think our library’s leadership team are all evil geniuses plotting to do bad things? No. But they do often make decisions without ever talking to the people who spend the most time with our students and faculty. Like literally none of us know why the libraries (which barely have anyone in them these days with the majority of classes online), are going to be open over Spring Break, forcing our poor Access Services staff to come in. AS staff weren’t involved in the decision and weren’t told why. That’s not a conspiracy theory. It’s reality. Do I think my dean conceals information on purpose to cause harm? No. I think she is a problematic communicator with too much on her plate and has apologized in the past for completely forgetting to send out meeting minutes and tell us important things. That doesn’t change that I would likely say yes to at least a few of those items and it also doesn’t change that those things totally suck. The authors do mention that organizational conspiracy theories can be true, but, then, what makes it a conspiracy theory if it’s factually accurate?

So they found that people who had low job satisfaction were more likely to agree with these statements. Hmmm… could that be because they’re dissatisfied with how leadership makes decisions and communicates? Is it possible that these are not conspiracy theories at all, but actual toxic leadership traits? I mean did this person read anything by Kaetrena Davis Kendrick, Alma Ortega, or countless other BIPOC library workers who have written about toxic leadership in libraries? Even if staff really do adopt negative explanations about how and why things are done, it’s probably because of the lack of honest transparent communication!

I am deadly tired of organizational problems being placed at the feet of workers, especially in light of the mountains of research that indicates that the burnout a huge percentage of workers are feeling right now is caused by (and can only be fixed by) their managers. If we burnout we’re not resilient. If we’re dissatisfied with management, we’re conspiracy theorists. Nowhere in this article does the authors suggest that perhaps management might be doing things wrong.

I’m also concerned with the questions they used to determine “organizational commitment.” These first ones seemed less focused on commitment to the particular organization than commitment to the ideal of the loyal company man of the 1950s who stayed at the same job his entire career. Of course, that career (even a blue collar one) paid a wage that allowed him to buy a home, comfortably raise a family with a single income, and retire easily with a solid pension. But cool, this is what organizational commitment looks like now:

- “I think that people these days move from workplace to workplace too often.

- I do not believe that a person must be loyal to his or her workplace.

- Jumping from workplace to workplace does not seem at all unethical to me.

- I was taught to believe in the value of remaining loyal to one workplace.

- Things were better in the days when people stayed with one job for most of their working lives.

- I do not think that wanting to be a ‘company man’ or ‘company woman’ is not sensible anymore”

These other ones read like a textbook definition of vocational awe or a book I read recently about codependency in the workplace. It seems to suggest that anything less than deep emotional enmeshment and slavish devotion to that workplace over any personal needs (even a better job!?!?) is not organizational commitment.

- “I do not feel emotionally attached to my workplace.

- I really feel as if my workplace’s problems are my own.

- I think that I could easily become attached to another workplace as I am to this one.

- One of the major reasons I continue to work here is that I believe that loyalty is important and therefore feel a sense of moral obligation to remain.

- If I got another offer for a better job elsewhere I would not feel it was right to leave my workplace.

- I do not feel like a ‘part of the family’ at my workplace.”

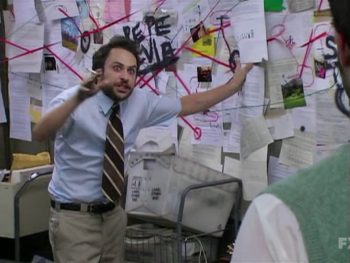

And oh lord, the old “family” thing?!? My colleagues are lovely people. I am friends with many of them. But family? No. Energy vampire Collin Robinson from the comedy What we do in the Shadows describes well in this clip how “we’re all a big family here” is weaponized against workers:

The article begins by quoting the author of the book Suspicious Minds: Why We Believe Conspiracy Theories saying that a conspiracy theory “portrays the conspirators as preternaturally competent; and as unusually evil.” This is another place where diagnosing most library workers’ resistance to change as acceptance of conspiracy theories doesn’t hold water. To me, these “conspiracy theory beliefs” sound more like ginned up versions of poor change leaders. If anything, most people who have bosses who are terrible communicators aren’t frustrated because they think their bosses are preternaturally competent and unusually evil. It’s because their bosses are incompetent (and perhaps also uncaring) and that incompetence is negatively impacting them. But even if people are spinning true conspiracy theories about their bosses, they are, as the authors themselves suggest, doing it because of a lack of clear information. This sounds a lot like a communication problem.

As someone who has actually extensively studied change leadership and published a well-cited scholarly article about it focused on John Kotter’s model, two critical aspects of change leadership are communicating a vision that speaks “to the things that make librarians value their work” and “engag[ing] with stakeholders.” I also wrote the following:

Resistance is a common force in any change initiative. While many early management researchers saw resistance as the cause of failures, more recent studies suggest that resistance is usually a symptom of problems with the change vision or its communication, and how change leaders respond to resistance determines the fate of the initiative. In fact, many scholars now argue that resistance can be a useful learning tool for leaders (Ford and Ford, 2009, 2010; Gandz, 2008).

Meredith Farkas, Building and Sustaining a Culture of Assessment: Best Practices for Change Leadership

Even the one change leadership expert they cited in the article, Todd Jick (and collaborators) wrote in a 2017 article about the importance of communication, engaging far-flung stakeholders, and not skipping steps in the change management process. They wrote “more and more, stakeholders expect to be heard and expect to have an influence on the outcomes of change, and there are more and more channels for multi-directional dialogue emerging.” What I think amazes me most is that communication is not mentioned once in this article as an important part of change leadership and maybe part of the problem (though of course the problem is the librarians’ thinking, not the change leadership, right?). I kept hitting command+f and searching for words like communicate, talk, discuss, explain in the hopes that they would recommend these very simple antidotes, but they did not.

So what is the point of this article really other than furthering the idea that unhappy library workers somehow have a stilted view of reality? The authors said it was about the “implications for change management and leadership,” but the only advice they really offer is that 1) it’s a good idea to work on people’s job satisfaction because it makes them more productive and 2) “national leadership institutes frequently cover change management and can be an excellent source of learning and improving leadership skills.” Groundbreaking. I know my eyes have been opened. There is a rich literature on change leadership and resistance to change (both in our profession and outside) that they could have drawn from (rather than a single book chapter written in 1990 — light years ago given how much that field has grown) and they didn’t. I truly do not understand what contribution this article is making to our profession other than being deeply anti-worker and writing off concerns about poor change leadership processes as “conspiracy theories.” At its best, it’s bad scholarship.

So now leaders, you have perfect cover for your terrible change leadership skills. Your unhappy workers are just deluded, much like the people who believe “the American moon landings were faked,” “the AIDS virus was created in a laboratory,” and “there was an official campaign by MI6 to assassinate Princess Diana” (truly those were also asked in the survey too). Nowhere do they even distinguish between the level of delusion between believing those three things and believing your bosses are making terrible decisions without consultation and are not being transparent. And here’s some more good news leaders! “Library leaders do not need to worry as much about employees leaving the library even if they believe in organizational conspiracy theories and have low job satisfaction.” So you should probably address their low job satisfaction, but if not, at least you don’t need to worry about them leaving.

The thing that really gets me is that conspiracy theorists are well known for being unwilling to consider other, more reasonable, possibilities. I feel like the same is true of the authors of this article. They have an almost pathologically myopic view and no other evidence matters. These authors went in wanting to prove that librarians who were dissatisfied with their jobs also believed conspiracy theories about their bosses and they literally didn’t consider that there could be another explanation; that maybe instead of believing “conspiracy theories” these people thought poorly of their bosses because their bosses were legitimately bad leaders. Can you imagine being a manager, looking at employees who are angry with you, and explaining it like this? Sounds like these managers experience “a lack of understanding…, a lack of control or uncertainty, or the need to keep a positive self-image.” Huh. I mean, even I can recognize that part of my anger about this piece comes from feeling unheard by management at my own library, but they can’t consider that maybe what they define as conspiracy theories is actually legitimate concerns about being left out of the change management process, a process that is actually supposed to include staff?

I honestly think that this article is beneath In the Library with the Lead Pipe and I think they should retract it, not only because it’s anti-worker and seems inconsistent with the values of the publication, but because it’s really poor scholarship. The editorial board writes that “Lead Pipe prioritizes marginalized people’s safety over privileged people’s comfort” but this article is a classic reflection of white supremacy culture and how it shows up in libraries. There is no sense of any understanding of the roles power and privilege play in people’s (especially those who have experienced oppression) relationships with and perceptions of their place of work. It is gaslighting, erasing experiences of toxicity and explaining low-morale as a belief in organizational conspiracy theories. This article does not “help improve communities, libraries, and professional organizations.” This does not “make a unique, significant contribution to the professional literature.” The Lead Pipe editors write “as part of our journal’s commitment to improving libraries, library work, and library-related scholarship, we expect all submissions to address how multiple facets of the author’s identity or positionality relate to their topic and article” yet I don’t see anywhere in this document where the authors talk about their positionality and how one of them is an Associate Dean at a major research university. How can they pretend that their position in their library doesn’t impact how they see this issue, especially when they can’t even acknowledge other explanations? And yet it’s not even mentioned. For all of these reasons, I call for In the Library with the Lead Pipe to retract this article.

Excellent review of a terribly problematic article. Only 1 of their already restricted n actually IDed as a ‘conspiracy theorist,’ so how are conclusions drawn there? What were their control variables? I want to know how race and gender controls (if they even had them, no mention in the article) correlated with answers–it seems very obvious to me that there would be some significant effects there because libraries have already been exposed as toxic & racist. Was there any control for management status of the librarians? (Faculty status doesn’t preclude differences in places in the administrative hierarchy, and I would have expected a control for ‘in a management position’ or something similar.) Were there any moderating variables? In the averaging of respondents’ scores, I didn’t see any standard deviation information. The thematic coding of the open response item is seriously problematic – what exactly were the parameters or operational definitions for coding overlapping concepts like “like my colleagues,” “good environment,” and “enjoy the work”? I know librarianship has a record of not training its professionals in research methodology, but this…this made it past an editor (per the thanks at the end of the article).

The yikes factor here is statistically significant with a large effect size.

Meredith, your blog posts are always interesting and thought-provoking, and this is another wonderful example of how important it is to push back when something is as wrong as the article in the Lead Pipe is. The article should absolutely be retracted, and I too am disappointed by them for letting such poor scholarship get through the gates of their publication. Thank you for taking the time and effort to post this here. I totally agree with your assessment.

Thank you for writing this.

You may already know about this website but I was looking to cite the “White Supremacy Culture in Organizations” handout I received at a SURJ meeting a few years ago and found this website which was created last year. https://www.whitesupremacyculture.info/

Oooh, I hadn’t seen this website! I’ve read the original work from 1999 and the one from the Centre for Community Organizations, but this is fantastic! Thanks so much for sharing Merrilee!

The original article, and this specific and trenchant critique, really hit home. I am not a librarian, but I work with several dedicated ones at my major research university. Not to give away too many details, but I can confirm the chasm of distance between the original article’s frankly dehumanizing claims on one side and the on-the-ground realities of the library on the other side. Virtually zero awareness among administrators. And the original article’s imperious tone also points to problems beyond personnel: even decisions about space allocations reflect some administrators’ desire to CYA and make themselves look competent above all else. So, for instance, when I pointed out via social media a couple of years ago that there was a huge amount of space in which (mostly white) students were spread out gaming, but there was only a tiny (<200 sq ft) space in which mostly students of color were working with writing center consultants, the backlash from library admin and the public relations office was immediate and fierce. I'm a tenured faculty member outside the library, so I didn't care that they tried to call me out for tweeting an obvious disparity. What I did–and still do–care about is that beyond their knee-jerk response and a "let's meet over coffee and talk about this" with an administrator, there was no interest in actually doing anything about the disparity. Still isn't, from what I can tell.

So, yeah, Meredith. Thank you. I didn't realize somebody got a "publication" out of this kind of BS. I value academic librarians immensely, and I will do all I can to make sure they are actually heard. And I'll be following you from now on!

Thanks for having our backs! It’s always amazing when faculty understand what we do and support our work. Yeah, I’ve worked with a lot of professional administrators whose main focus seems to be doing things that will look good on their resume so they can get the next better job (though I’ve also worked with a few fantastic and devoted administrators who were truly focused on supporting students). So the focus is not on doing good or supporting the people beneath them on the org chart, but on doing big, flashy, innovative things that will look good to folks on the outside. A ton of the most valuable work in academia that will improve equity for students are not at all flashy (like your example or making tweaks to systems or course design) and that is just never going to be a priority for those professional administrators because it won’t move the needle forward on their careers.

The Lead Pipe authors surveyed three academic libraries in Utah. Now, I personally have nothing against Utahns, but the state is not representative of the rest of the US: a quick google search says, “According to 2017 demographics estimates population of Utah by race are, 86.84% are White Americans(2.6 million), 13.67% are Hispanic/Latino’s, 2.2% are Asians, 1.1% are Black Americans, 0.8% are NHPI, 1% are AIAN.” Yep, that survey can surely tell us a lot about a small group of white people.

For sure! It’s ridiculous to only administer the survey at just a few academic libraries in a single state. But even if it were an incredibly representative sample of library workers, the whole premise of the survey and the survey instrument were ridiculously flawed.

I read the full article before reading yours. WOW. Thank you. I came away shocked that it somehow was published. Everything you mentioned…I was right there with you.

Leadership and Organizational Change is bursting with theories and sound applications for employee satisfaction. As an administrator, I know how poor the communication channels are and can break down. But if leaders and managers and supervisors (for me they are separate and not all the same at all times) can’t take responsibility for our own shortcomings and expect of ourselves the same we expect of our colleagues, trust-communication-agency-validation-belonging will stall or not reverse course. OK…I’m rambling now because that just got me going…

Thank you for writing your response and calling for the retraction.

#InSolidarity

Thanks for your comment Oscar! It’s really nice to hear that a library administrator saw this similarly. I feel like the article does nothing but further erode trust between admins and staff and I’m glad you’ve also recognized the toxic impact of poor communication in orgs (especially when the administrator doesn’t own it).

I have done some investigating about toxic leadership, and was surprised that this title was not included in the list of references: “Academic Libraries and Toxic Leadership”, 2017

by Alma Ortega