In my last post, I wrote about the absolutely monstrous difficulty I was having getting off the migraine prevention medication (that wasn’t actually preventing migraines) I had been taking for 11 years. I saw two doctors and a sleep specialist about the issues I was having and none of them were helpful. My interactions with my regular doctor were especially demoralizing. She gave me a medication that was supposed to help me sleep and when that didn’t work, she left me to my own devices. She’d told me to follow up with her via email about how things were going, but she never responded to me. I made an appointment with her as well, but it was 4 weeks away. As I’d mentioned, I finally gave up and started taking the medication again which immediately fixed my sleep and stomach issues (because it’s really hard to live when you can’t eat and only sleep 3 hrs per night — go figure).

When I finally visited my doctor, her response to me was basically “this shouldn’t happen with this medication.” Never mind the fact that it was happening. Never mind the fact that people have very different responses to medications that screw with their neurotransmitters. Her only suggestion was maybe to take a different drug in the same class (with slightly lower, but still present, risks of dementia and other neurological conditions) and that she’d check with their resident PharmD to see if that was a good solution. I left without any treatment plan; just the promise of one. And I never heard back from her. I emailed her multiple times. I called and was on hold for over an hour and the nurse promised my doctor would get back to me with answers. She didn’t. I called again and was on hold for over an hour and again talked to the nurse. This time at least the doctor emailed me back, but her response was that the PharmD didn’t think it would be worth switching to a different drug in the same class and that they both thought I should just taper down slowly (which I’d been trying again over those many weeks and it was just as much of a disaster as the first time). When I responded to her email to tell her it wasn’t working, she never wrote back. She left me feeling ashamed because if people should be able to get off this medication without difficulty and I can’t, I must be weak. She left me feeling less than human because she left me (after three visits and multiple emails and phone calls) totally without a treatment plan. I felt bad enough from the withdrawal I was experiencing, but the shame I felt on top of it was almost worse. I honestly felt like giving up and accepting that I would just be on a harmful drug I didn’t need forever and resigning myself to ending up with dementia or Parkinson’s.

In the midst of not hearing back from her, I made an appointment with a psychiatrist because my own research showed that the medication I was taking impacted at least three neurotransmitters (and which one was causing my issues was a mystery) and I know getting neurotransmitters into balance is kind of their thing. My experience with him was night-and-day from the sleep doctor and general practitioners I’d dealt with. He was curious, empathetic, and open to experimenting with various drugs to see what might work. While he acknowledged that what I was going through was unusual, he fully believed me about what I was experiencing. We tried a few different strategies before we hit on one that seems to be working well. I’m down to taking 1/4 of the smallest pill of my medication and plan to try going completely off it in a couple of weeks. Every time I’ve had an appointment with the psychiatrist, he starts with “I’m really curious to hear how it’s going.” He made me feel like he was in it with me. Like he cared. Like I wasn’t alone. And feeling all that made me feel like I could get through this.

While it might feel like this experience has nothing to do with librarianship, I immediately saw parallels to my work as a reference and instruction librarian at a community college. A lot of students in a community college setting (and frankly also at other institutions of higher education) have had experiences in their lives that have led them to not believe in themselves. To see any sort of struggle as a sign that they’re not good enough and don’t belong in college. That shame isolates them. They can’t see that so many of their classmates have similar or even the exact same struggles. They can’t see that it’s often normal to hit barriers in doing research and that yes, library databases really are hard to use. When you’re living with shame, you internalize those struggles and beat yourself up. You don’t feel good enough. And I know all this because with my history of childhood trauma and in spite of the self-work I’ve done, my response to struggles in any part of my life is still to feel shame and beat myself up.

Because of my own experiences, I think a lot about student belonging. I’ve seen how things like not being able to schedule a meeting with their advisor, not understanding how to register for classes, not having taken textbook costs into account in their budget, trouble getting accommodations for a disability, not being able to print because IT’s system is crap, an unresponsive instructor, or even a difficult to navigate library website can alienate students (especially already vulnerable students) and prevent them from feeling like they belong in college. It can often feel like death by a thousand little cuts. And while I work at a college that claims to be deeply focused on EDI and belonging (they call it B-JEDI — <eyeroll>), I’ve seen students lose confidence in themselves and excitement about college as they constantly face bureaucratic barriers, even small ones that the college could easily address (like printing which has brought some PCC students to literal tears). Because, for so many students, not figuring out how college works or hitting barriers will lead to shame and self-blame. Feeling like you belong in college is critical to college success and that feeling is so very easy to crush.

How do you combat these feelings in students? Similar to my experience, having someone who helps to normalize what a student is struggling with and makes them feel like they’re “in it” with the student is key. And I don’t think it matters if that person is a librarian, a tutor, an advisor, their instructor, or even a peer; the act of having someone who is invested in your success and validates your experience is incredibly powerful. I was recently in a meeting for the Family and Human Services program Advisory Board (one of my liaison areas) at my college where some graduating students spoke about their experiences in the program. Their descriptions of their journeys left me with tears in my eyes. They talked about how being in the program changed their perceptions of themselves and what they could achieve. How having instructors with high expectations who also believed in them and were invested in their success made them rise to the occasion. The feeling of having someone else “in it” with you (even in very small ways like my psychiatrist was) when you’re struggling is deeply powerful antidote to the isolation and self-blame that shame brings.

In my own work, I really try to validate as much as possible that research is hard. I can’t tell you the number of times that students have commented that it felt so good to hear from me that, yes, our databases are a pain-in-the-ass to use or how refreshing it was to see me struggle with a search or to come up with the keywords that best describe a research topic. I remember when I first started teaching 18 years ago, I would prep for classes by coming up with “perfect” combinations of keywords to get excellent results lists when I searched in library databases. Now, I find the best thing I can do is model the very normal messy trial-and-error of figuring out what keyword combinations will get good results and the very real challenges of using databases. If students see the librarian effortlessly searching and they have no luck finding sources themselves, many will internalize that and will convince themselves that they aren’t capable of using library resources. I feel like anything else I could possibly teach students is far less important than just normalizing 1) research often being hard and 2) asking for help. It always makes me giddy when I hear from my colleagues that a bunch of students from a class I worked with have been making research consultation appointments. While I know that could be viewed as a failure of my teaching, if students felt safe enough to seek help (something I never did in college), I know did something right.

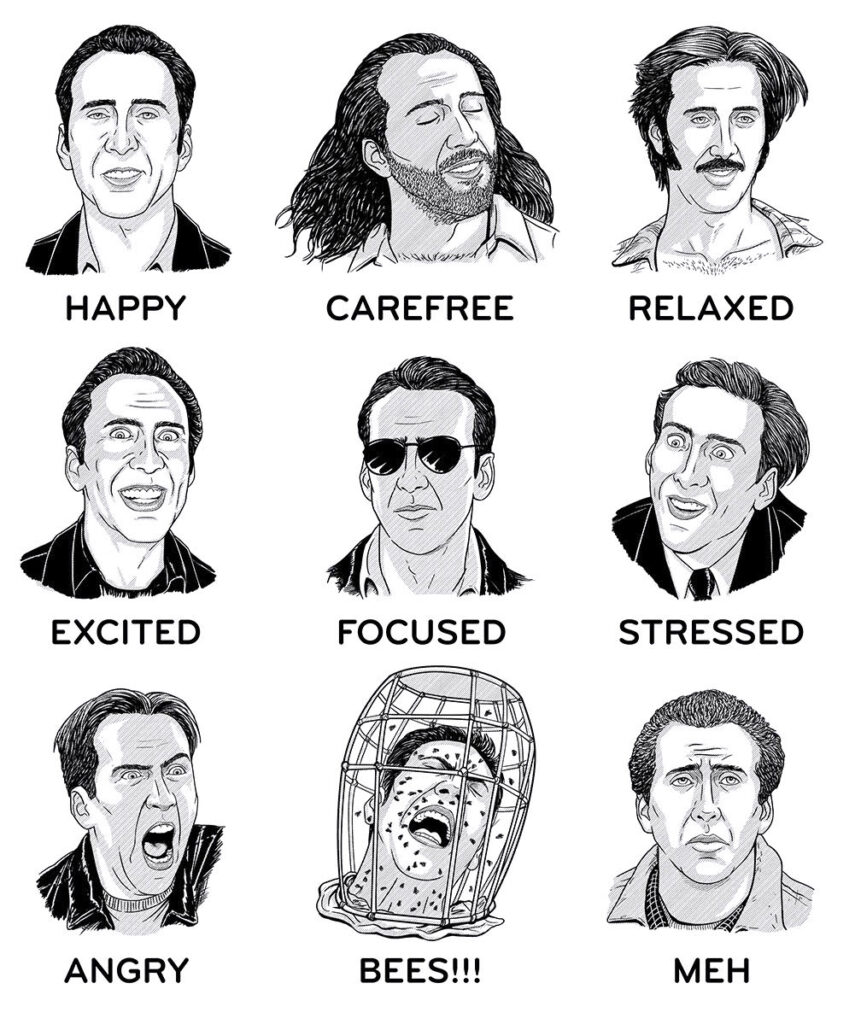

In addition to just modeling hitting barriers, I do activities with students that seek to help students reflect on the things they’re good at, ways they could improve their skills, and that encourage being patient with and kind to oneself in the research process. I often begin classes with an icebreaker of some sort and I particularly like to use the Nic Cage Gauge At the start of an online class session, I show the gauge and ask students to type how they’re feeling in the chat. From that, I get into talking about how our emotional state impacts our ability to do research — how when we’re stressed, we’re less likely to have capacity or tolerance for roadblocks in our research, etc. I encourage students to take an inventory of how they’re feeling when they’re working on a project and to be easy on themselves when they’re feeling stressed/bees/angry/meh/etc. If they can break the project up into smaller pieces (and I acknowledge that not everyone has the time and space for that), it will help on those days when they just don’t have it in them to power through a lot of it. It also can feel good when you’re feeling bad to accomplish one small, manageable task than to beat yourself up for not making more progress. I talk about myself and how I used to be very hard on myself when I didn’t have it in me to do something on a particular day (and I’d try to muscle through it which was awful), but that I actually find myself happier and more productive when I pay attention to how I’m feeling and honor that. Students get so busy and stressed that they often ignore how they’re feeling, so getting them to do some reflection and to think about how their affect might impact their research feels important.

Another activity I do gets student reflecting on their own research skills. The goal is to for them to both learn from their own reflection and from the anonymous aggregated reflections of their classmates. It’s based loosely on the amazing Information Literacy Reflection Tool (ILRT) created by my brilliant PCC colleague Sara Robertson, two other amazing Oregon librarians (Michele Burke and Kim Olson-Charles), and a psychology professor (Reed Mueller). If anything, what I do is an insult to the ILRT because they did all this amazing work to statistically validate the statements in their tool and I just pick and choose the pieces that I want to use. I grab 10 statements from the ILRT that I think are the most interesting and relevant to the class I am working with. I ask students to complete a Google Form where they look at those ten statements and select one that they think describes them best (the one they feel most confident about) and the one they think least describes them (the one they feel they most need to work on). I also asked them to share how they got good at the thing they said they felt confident about. Before they complete it, I share my own responses to the questions, modeling that I also struggle with things (keeping my research organized, still a nightmare for me). Once they’ve filled out the form, I share and discuss the anonymous responses with them, showing that students struggle with (and are good at!!) all different aspects of research and that it’s totally normal to hit roadblocks. They also could see how other students got good at the things they felt confident in (a lot of great themes came up like practice, breaking work up into manageable chunks, learning from another classmate, trial and error, a librarian showing them something, etc.). I hope this also reminds each student that there is/are some aspect(s) of research they are actually good at.

After that, I ask students to share in a Padlet one thing they “can try this term to get better at the research skill you felt you most needed to work on.” The responses were really great! Here were a few choice quotes from one class:

- “instead of beating myself up over frustrating research, I’ll take a break and go on a walk. Clear my head and try again, calm.”

- “I am going to try to have grace with myself when I struggle to get organized.”

- “Ask for a second opinion, take more notes, and be more kind to myself.”

- “Working on the research and paper bit by bit rather than hyper-focusing on it all at once. Also, making a reference list as I gather information rather than waiting until the end to compile it.”

So many responses from students have been around breaking up their work into smaller manageable tasks, asking for help, talking with classmates, and not beating themselves up when they hit roadblocks. It’s been incredibly heartwarming to see how earnestly students have participated in this activity.

But it’s not just in our teaching where we can make a difference and foster belonging. We can also look for pain points — places where students hit roadblocks or where the library perhaps is not as welcoming or user-focused as it could be. One of the recent projects I’m most proud of is our redesign of our library databases page. The databases page had been my biggest source of annoyance since I came to PCC nine years ago, but I wasn’t able to create a sense of urgency for others until I led a student needs assessment in Winter 2022 that surfaced what a problem the page was for our students. While the changes made to the page are not super-innovative and will probably not blow anyone’s mind but my own, they are going to have such a huge positive impact on our students because they will make it so much easier to select the right database for their project. I’m immensely proud to have been able to contribute to this work with my fantastic colleagues in Reference and led by our colleagues in Digital Services!

I’m a perpetual work in progress as an instructor and reference librarian and am always trying new things in my work with students. But more than literally anything, I want to communicate my genuine care for them. So more than teaching specific databases, search techniques, or threshold concepts (all of which I do too), I think about “how I can show this student (or group of students) that I’m invested in their success? How can I show that I’m ‘in it’ with them?” As a librarian, I don’t think I’m going to radically change a student’s life, but I know that a feeling of belonging (or alienation) in college is made up of a thousand small experiences and I want their experience with me to land on the side of belonging. I never want to be for someone else what my regular doctor has been for me.

Your blog posts are so amazing.

I’m a Community College Librarian and everything you said is so true. I remember helping an adult student that was trying to do business market research and English was her second language. I said “this is hard for everyone!” and I could tell it made her feel so much better.

I’ve had health struggles in the past year and it’s all due to an allergy that comes from a tick bite (alpha gal syndrome). Medical professionals know very little about this and have almost no solutions. I got help on my own (specialized acupuncture for allergies). But feeling that helplessness and having to figure all of that out on my own was terrifying.

My mindfulness practice has been life saving, but it can only do so much.

Thank you, thank you, thank you for sharing all that you share. I value every word.

Thank you so much for the kind words Jennifer! It’s so heartbreaking when we can clearly see that a student thought they were the only one struggling with something and so beautiful when they finally realize they’re not. I’m so sorry to hear about your health issues, but I’m glad you’ve taken your health into your own hands (sucks that we often have to do that!) and are getting some relief. Here’s hoping for better health for both of us in the next year!